ave imperatore, morituri te salutant

by justin saint-loubert-bie

Hail, Emperor, those who are about to die salute you – Roman gladiatorial salute

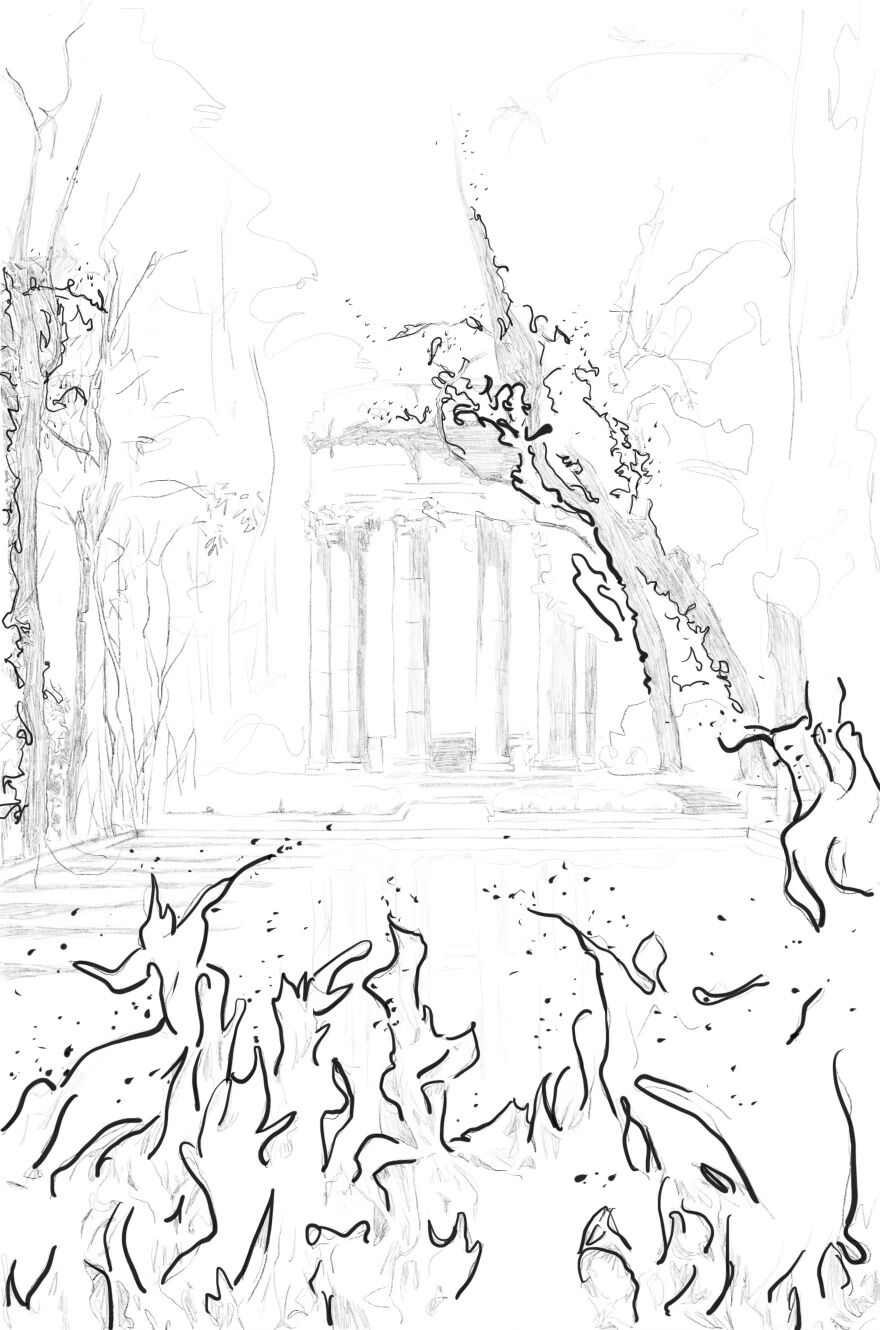

The apocalypse is a fitting time for Roman architecture.

Just a few weeks ago, the reflecting pool laid out at its feet would have glowed orange. On most days the pool still frames a pale, sickly haze. Now the reflection is blue again, but I need to cast my gaze over a cloth mask, through fence bars, and over a wide lawn to catch even a glimpse of what I came to see. The Pulgas Water Temple is closed indefinitely due to Covid-19. Hiding in the Northern Californian hills as fire and plague batter the state, the Pulgas Water Temple is the ultimate monument to civilization. Just not for the reason its designers intended.

The story of the Pulgas Water Temple also begins with a conflagration. Water shortages have long plagued the settler colonial state of California. For San Franciscans, the true precarity of their situation was driven home in 1906, when an earthquake ignited a fire that would consume much of their city. The blaze was so serious partly because San Francisco’s water system was unreliable, and the earthquake had largely debilitated it. Two years after the disaster, San Francisco petitioned the federal government for water rights to the Hetch Hetchy valley in the Sierra Nevada Mountains. The 1906 fire was fresh in the minds of San Franciscans, but a reliable source of water would also be critical to the residential and commercial expansion of the city.

Congress debated the request for several years. After all, in 1890 the Hetch Hetchy valley had become part of a brand new legal entity, the first of its kind: Yosemite National Park. In theory, national parks were supposed to protect the beauty of nature for future generations. It was on these grounds that the Sierra Club fought desperately to prevent the damming of Hetch Hetchy during these years. John Muir, a founding father of Yosemite National Park—and indeed of the very concept of a national park—led the charge. “Dam Hetch-Hetchy!” he wrote. “As well dam for water-tanks the people’s cathedrals and churches, for no holier temple has ever been consecrated by the heart of man.” But all of this work would be for nothing. Eventually Congress made up its mind, and President Woodrow Wilson signed the bill to dam Hetch Hetchy in 1913.

And so the ponderosa pines, lupines, willows, Douglas firs, buttercups, poplars, and black oaks were all drowned. The black bears, bighorn sheep, and mule deer were driven from their homes. The year was 1923.

But in addition to an ecological disaster, the damming of Hetch Hetchy was also a human catastrophe. Of course, neither the Sierra Club nor John Muir, and certainly not the federal government, paid any attention to the importance the valley held for Indigenous people. After all, the United States government has rarely been a friend to First Nations, and early conservationists were often happy to forcefully remove Indigenous people from their lands in order to establish national parks.

Although the colonial record is insufficient to reconstruct the history of the Hetch Hetchy valley itself with complete certainty, ethnohistorian Brian Bibby identifies several Indigenous communities with historic relationships to the the lands now contained in Yosemite National Park, including the Central Sierra Miwok, Southern Miwok, Bridgeport Paiute, Mono Lake Paiute, Owens Valley Paiute, Chukchansi Yokuts and Western Mono. The damming of Hetch Hetchy robbed all of these communities, not only of the material resources contained within the valley, but also of a portion of their ancestral homes and a traditional way of life inextricably coupled to the land. Colonial powers had waged an extended campaign of destruction in the region for decades, an asymmetric warfare whose tactics included forced missionization, the spread of diseases, child abduction and reeducation in Indian schools, and even the creation of Yosemite National Park itself, which barred Indigenous peoples from living on their own lands within the boundaries of the new park. The damming of the Hetch Hetchy valley was the climax of this genocidal rampage, an act of criminal theft accomplished through the United States’ raw imperial power.

Damming Hetch Hetchy was a catastrophe for Indigenous people, but for San Francisco it was only half of the battle. The city now faced a simple but intractable problem of geography: San Francisco lies on the western extremity of the third largest state in the union, while the Hetch Hetchy Valley is cradled in the Sierra Nevadas in the eastern part of the state. The Hetch Hetchy Aqueduct, completed in 1934, was the solution to this problem. To this day, the Aqueduct extracts water from the Hetch Hetchy reservoir, cuts for 160 miles under the California ground, and disgorges its plunder into the Crystal Springs Reservoir a few miles south of San Francisco. Where the Aqueduct and Crystal Springs Reservoir intersect, the city of San Francisco erected the Pulgas Water Temple in 1938.

Now, the water from the Aqueduct is diverted to a nearby treatment plant to comply with updated environmental standards, before being emptied into the reservoir at another spot. But once upon a time, visitors could look down through the well at the center of the Temple and see an offshoot of the Hetch Hetchy River cascading over a small waterfall, flowing, bouncing, giggling and gurgling through an open-air canal, before finally ending its odyssey with a cold, clear, and gleeful splash.

This historic junction between wilderness and city is what the Pulgas Water Temple aims to celebrate. “I give waters in the wilderness and rivers in the desert, to give drink to my people” (Isaiah 43:20). You can read these words—on a day the grounds are open—in the stone circlet that crowns the Temple, beneath an ornate ring of gargoyles and fleurs de lis. Ten columns dive down from the quotation, each column horizontally segmented and carved with vertical grooves, free falling for a couple dozen feet before plunging into a large pedestal raised above the surrounding lawns. The whole structure looks a bit like a peg, albeit a monumental and beautiful one. The center of the Temple is open air, and the central well takes up most of the available space. Inside the well, above its metal grille, a bronze plaque repeats the quote from Isaiah. William Merchant—the architect—won’t let us forget what his shrine is devoted to: the union of wilderness and city.

But this wilderness is a colonial one. Its dearth of humanity is based on a violent emptying by plagues, abductions, and dams. The very concept of wilderness is often colonial, because places that were genuinely unoccupied by humans before European imperialism are few and far between. Many National Parks are uninhabited today only because of the guns of United States armymen. Yosemite National Park is no exception. Nature abhors a vacuum; only empires create voids. Once manufactured, these newly vacant spaces, through their power of suction, draw to their bounty the metropole, the city, civilization.

This is what the union of city and wilderness really means. It is a process of imperial extraction that can only come after the extermination of the communities to be commodified, the conscription or destruction of their human and nonhuman components in forced regimes of radical simplification. Violence lies at the root of the plunder of Hetch Hetchy’s water. This is what the Pulgas Water Temple really celebrates.

Fitting, then, that it should adorn itself in the trappings of Rome, an empire that at its peak enslaved, taxed, or otherwise controlled 20% of the world’s population. Nominally, the Temple’s design honors the Roman aqueduct technology that made the Hetch Hetchy Aqueduct possible. But more fundamentally than that, the monument pays homage to the West’s newest empire through an architectural nod to its oldest one.

On a sunny day like today, the reflecting pool only mirrors the cypress trees that line it and the columns of the Temple behind. But it’s impossible to forget that I’m only here because, for the first time in a week, the air isn’t chemically toxic. I can’t even step onto the grounds, which is an acute reminder of the biological toxicity that, at the time of this writing, we’ve lived with for over two years.

How appropriate that the flames and diseases that imperialism set loose upon the world have finally caught up to its monuments. After torching and infecting the Americas, the logic of imperialism now finds itself caught in a trap of its own making. Colonizing the atmosphere with its pollution, it accelerates climate change and the fires in California. Cramming animals and people together in brutal regimes of forced labor, it sets the stage for the next pandemic. Perhaps we are witnessing the beginning of the end of empire. Unfortunately, we may not live to see what comes after.

Why do we still build in the Roman style? It may seem strange—perhaps comically ironic—to adorn our most important buildings with the trappings of an empire that, in the final analysis, failed. In fact, it’s a remarkable act of unintentional self-awareness. Empire built the world we know today. But empire is also destroying it. Through fire and plague, the Anthropocene is truly upon us in California, and now might be a good time to think about the fall of the Roman empire. Because if we are unable to finally learn the lessons of two thousand years of history, the next set of Roman ruins may be our own.